Urban challenges: homelessness in Brussels

Like most big cities, Brussels faces a number of challenges that affect the welfare of its inhabitants. Today, Belga English examines homelessness in the Belgian capital. What are the main issues and what is being done to tackle them?

According to censuses carried out by organisation Bruss'help, which coordinates emergency aid and integration assistance for homeless people in Brussels, the homeless population in the city has more than quadrupled in 14 years. The first census in 2008 counted 1,724 homeless people. By 2022, their numbers had risen to 7,134, and that is probably still an underestimate.

A significant proportion of Brussels' homeless people are undocumented migrants. In recent years, many people in poverty or with mental vulnerability have also ended up on the streets because of the Covid, energy and economic crises.

The number of vulnerable profiles is increasing. There are more elderly people and people with chronic diseases such as diabetes or cancer on the streets. Health surveys show that almost four in 10 of the people sleeping outside have mental health problems such as psychosis, depression or addiction. The number of women, single mothers and unaccompanied minors is also rising every year.

Shelters and housing initiatives

When asked about the rising figures by news outlet BRUZZ, Brussels minister for health and social action Alain Maron called them “worrying” and said much of the increase was linked to the shelter crisis and the rise in the number of undocumented migrants.

He added that despite the rise in the number of homeless people, the number was not increasing in public spaces. “This confirms the fact that we have significantly increased the supply of housing and shelter facilities during this legislature,” he said.

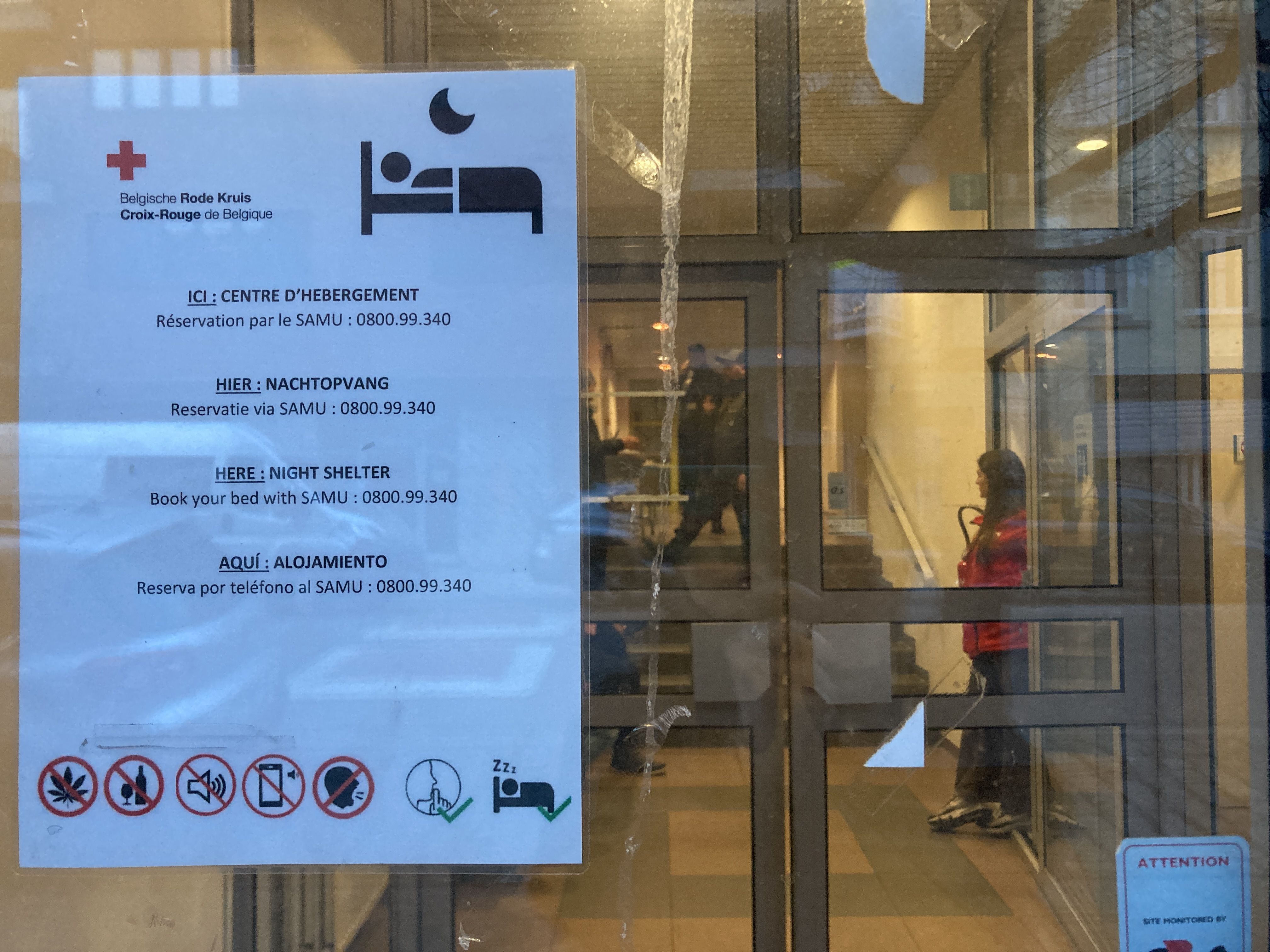

A total of 5,045 places in shelters are provided in Brussels throughout the year, including 3,084 in emergency shelters. There are also 937 places in projects for temporary occupation of empty buildings and 1,024 places in relief centres for homeless people.

At the beginning of 2024, the federal government released 3 million euros for 25 projects under the Housing First call for projects, aimed at helping homeless people find permanent housing. The projects in Brussels are led by the organisations SMES, Diogenes, Capuche and OCMW Brussel.

A network of non-profits

Many organisations have been helping the homeless in Brussels for years. Big names include Doctors of the World, the Belgian Red Cross and Samusocial. Less widely known is Doucheflux, which mainly offers showers and clean clothes, with the intention of restoring people's energy, dignity and self-esteem so they can start rebuilding their future.

Another important non-profit, Straatverplegers (Street Nurses), was founded in 2005 by two nurses who were shocked by the huge problem of homelessness in Brussels. Using a methodology based on hygiene and health, the organisation builds a bond with the most vulnerable. It has teams on the streets and teams that visit formerly homeless people, while another team looks for or helps create housing opportunities.

Plan to eradicate homelessness

In April, Bruss’help proposed a master plan to end homelessness in Brussels by 2029, as a guideline for the next government. The plan consists of 35 measures divided into four phases: strengthening prevention, improving rapid action, optimising support and combating institutional violence.

"The main focus now is on emergency shelters," Bram Fret, vice-president of Bruss'help, told BRUZZ. "That is certainly necessary, but with the master plan, we want to encourage the new government to invest in long-term solutions."

The organisation will make proposals to moderate rental prices, combat discrimination and create suitable and accessible housing for large and disadvantaged families. It also plans to draw up cooperation protocols with the health and prison sectors.

‘A political choice’

According to the plan, rapid action is needed to reduce the time a person spends without a place to live, to prevent the situation from becoming permanent and the lack of housing causing other problems.

One way to do this is to increase the number of sustainable homes and redefine the system of emergency shelters. Two-thirds of emergency shelters should be transformed into transit places, so people don’t stay there too long and enter the regular network more quickly.

Support for homeless people should also be optimised and “respond to any problem, including addictions and mental health”. The final stage is fighting institutional violence and injustice. Bruss'help wants to introduce ethical and socially acceptable support procedures to avoid "over-intervention and invasive or paternalistic" interventions.

"The reality is that things are not improving in Brussels, so it is the duty of all governments to take extra steps," said Elke Van den Brandt, president of the college of the Flemish Community Commission, which manages Flemish affairs in Brussels.

"It’s a political choice. No homelessness sometimes sounds like a difficult ambition, but it is a viable option. It just requires a lot of investments from both the government and actors in the field."

*This analysis is based on reporting by Brussels news platform BRUZZ

A homeless person's tent near the Poverello shelter in the Marolles neighbourhood of Brussels © BELGA PHOTO JONAS ROOSENS

Related news